Hedgehog mushrooms grow hunkered in clusters throughout the spruce forests of Afognak Island, north of Kodiak within the Gulf of Alaska. This fall, I tromped through thick moss to harvest these tasty fungi. It’s the abundance of Afognak’s forest that always beacons me back, but for many, including a visitor named Livingston Stone who came in the 19th century, it’s the salmon that make this place special.

At Afognak, the proverbial forest and stream come together in a historically significant way. In 1892, President Benjamin Harrison issued an executive order to create the Afognak Forest and Fish Culture Reserve. Not only was it the first forest preserve in Alaska, it was the earliest iteration in the USA of a federal conservation ethos that morphed into the National Wildlife Refuge system. The reserve was created not to conserve forests, but to protect the arboreal spawning grounds of what was seen as an at-risk resource- salmon.

Livingston Stone was the person who proposed the reserve. He was a founder of the American Fisheries Society in 1870 and the Deputy Commissioner of Fisheries for the U.S. Fish Commission (the predecessor of NMFS). He directed the construction of the first federal fish hatchery in the nation in McCloud, California in 1872. In 1889 he traveled to Alaska to research salmon and observe commercial fishing practices. On his trip north, he was disturbed to watch beach seines harvest 153,000 salmon over one day at the mouth of the Karluk River, watching only a handful of salmon escape to spawn upstream. He lamented canneries processing fish on the Nushagak River while not leaving enough for local Natives to subsist through the winter.

In a paper presented to the American Fisheries Society in 1892 and reprinted in Field and Stream and other widely-read publications, Stone alerted the nation to the snowballing threats to salmon survival. He wrote of the hastening degradation of salmon habitat in the west, drawing a comparison to what had occurred to Atlantic runs.

“It was the mills, the dams, the steamboats, the manufactures injurious to the water, and similar causes, which, first making streams more and more uninhabitable for the salmon, finally exterminated them all together. In short, it was the growth of the country, and not the fishing, which really set a bound to the habituations of the salmon on the Atlantic coast.”

Stone was more familiar with salmon conservation than most anyone else in the 19th century. Thus, he spoke with authority when he claimed,

“I will say from my personal knowledge that not only is every contrivance employed that human ingenuity can devise to destroy the salmon of our West coast rivers, but more surely destructive… is the slow but inexorable march of those destroying agencies of human progress, before which the salmon must surely disappear as did the buffalo of the plains and the Indians of California.”

Stone said that thirty years before, it was unimaginable to think that the buffalo would be on the brink of extinction. He warned that salmon were on a similar trajectory. And like the buffalo, which required the safe haven of Yellowstone National Park to protect the species from the encroachment of industry, salmon needed a place at which they too could be left unmolested. “There is no altar of refuge for the salmon in this country any more than there was for the buffalo.”

Stone claimed that the continental US was already too degraded to support such a reserve. But he had a place in mind that he had visited while in Alaska in 1889, Afognak Island. “It is easy to see what a paradise for salmon this island is, and what a magnificent place of safety it would be if it were set aside for a national park where the salmon could always, hereafter, be unmolested.” President Harrison agreed and created the reserve just several months after Stone initially delivered his speech.

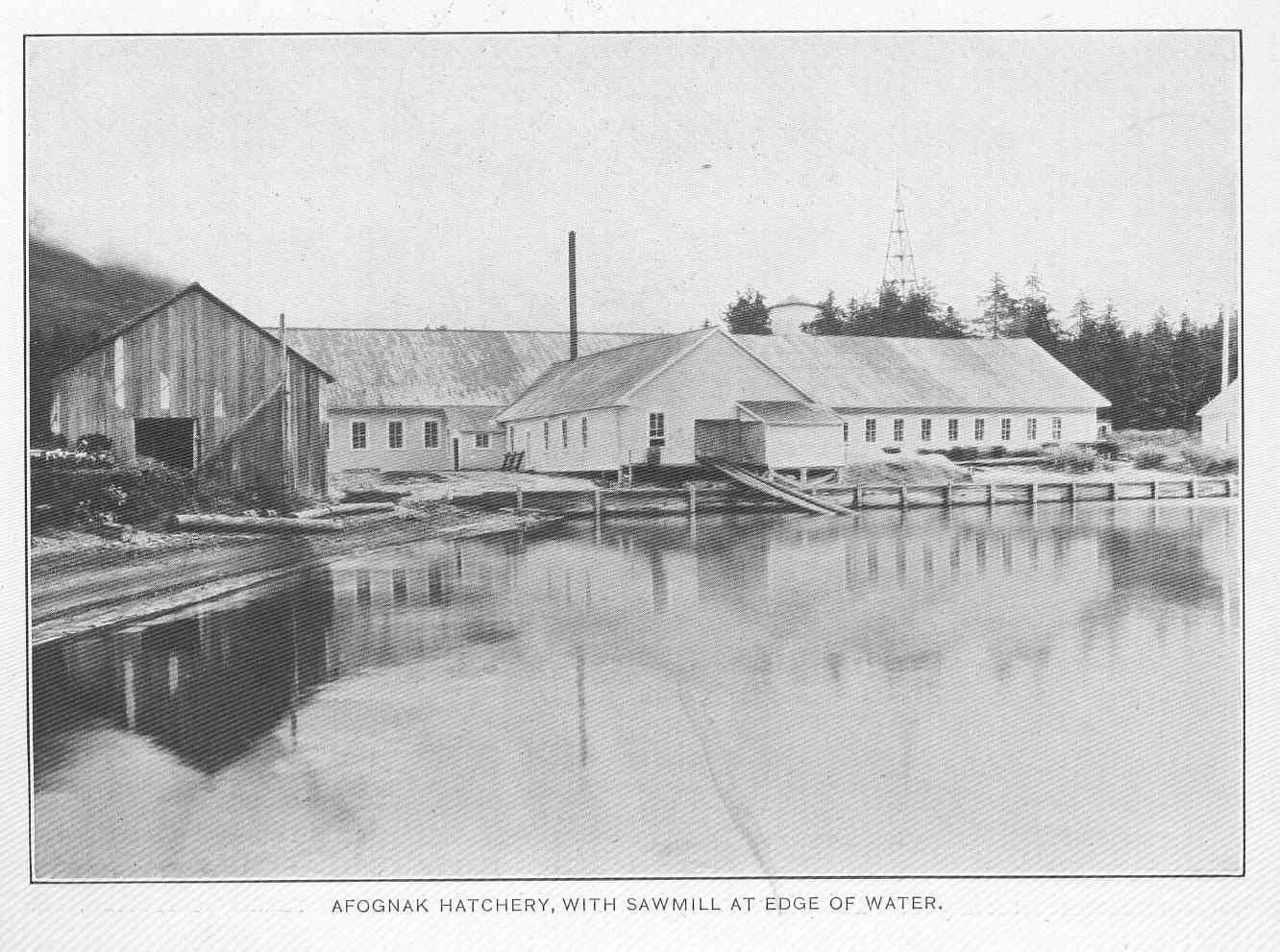

Stone acknowledged that Afognak was not the realm of just fish and forests. Indeed, Alutiiq Natives lived in both the substantially-sized community of Afognak Village and the smaller Little Afognak. Stone asserted that “there would be no injustice done to individuals by making a reservation of the island,” but this was not the case. The two canneries on Afognak Island were shuttered. But more significantly, Afognak residents were barred from fishing for either commercial or subsistence purposes on the island or off shore until a fish hatchery was constructed. Although Stone had lambasted processors on the Nushagak for not leaving enough fish for Bristol Bay Natives and had mourned the supposed disappearance of Indians from California, the reserve for which he advocated left no provisions for the Alutiiq people who lived on Afognak and most relied upon its salmon.

Photo from Bureau of Fisheries publication and made available here.

It took fifteen years to build the requisite hatchery, and even then Natives could only fish under the supervision of the hatchery superintendent. In 1912, a full twenty years after the reserve was established, Afognak residents were given the sole right to legally and independently fish within the reserve for both subsistence and commercial purposes.

In 1908, the Afognak Forest and Fish Culture Reserve became a part of the Chugach National Forest. After 1929, fishing regulations on Afognak coincided with those issued for the rest of the region. Much of the original reserve was selected by the Afognak Native Corporation following the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act and became corporate property. Today, the north of the island is part of the Afognak State Park. There, old growth spruce forest, abundant wild mushrooms, and ADF&G-managed salmon runs still pay homage to Stone’s vision.