Last month’s column described how salmon canners outsourced the recruiting and managing of cannery workers to labor contractors, the earliest of whom were Chinese. Unions came to replace the labor contracting system during the Great Depression, a time when wages for low-skilled cannery workers fell 40%.

Asian-Americans eager to procure labor contracts for themselves organized ethnicity-based groups for negotiating with contractors and canneries. Chinese, Japanese, and Filipinos each had their own organizations. In 1933, Filipino workers in Seattle joined the American Federation of Labor’s Cannery Workers and Farm Laborers Union (CWFU) Local 18257. This was a Filipino-only union, dedicated to advancing the needs of the Seattle Filipino community.

Initially, this early union was not much different from the other ethnicity- based workers’ organizations that came before it. Yet change was afoot. The labor contracting system’s unsavory reputation forced canning companies like the Alaska Packers Association to move away from contractors. The press publicized instances of egregious abuse. This helped the CWFU gain membership. But it was the murder of CWFU organizers Virgil Dunyungan and Aurelio Simon in Seattle in 1936 that convinced many laborers to abscond from the contracting system, since people believed that corrupt labor contractors had ordered the murders.

Unions then replaced labor contractors. In 1937, CWFU affiliated with the CIO and became Local 37 of the United Cannery, Agricultural and Packinghouse and Allied Workers of America. This affiliation brought into one union all of the separate ethnic groups that had previously attempted to negotiate with contractors and canneries. Henceforth, many canneries accessed employees through Local 37 instead of through labor contractors.

There were several marked improvements that came with union membership. Workers had written contracts with the union, while with labor contractors these agreements were frequently just verbal. The contracts specified working conditions and wages. Moreover, employees were paid by the cannery, not the intermediary contractor. In 1932, common cannery laborers received $25 to $50 per month. In 1939, after the unionization of cannery workers, laborers received $80 to $100 per month. It is worth noting that this increase wasn’t due only to better negotiated contracts, but also due to New Deal legislation which mandated an increase in workers’ wages.

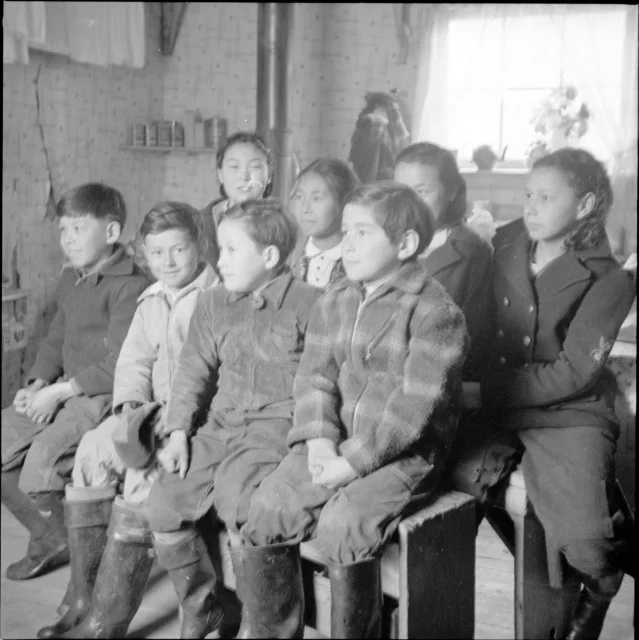

Unions made serious strides to improving worker safety and pay. Nonetheless, the industry remained segregated and the purview of Local 37 never extended beyond the realm on the Chinese cannery workers in the previous century. The “China boss” who had been responsible for keeping cannery workers in line during the era of labor contractors became the “Filipino foreman,” responsible for managing the Asian American canning crew. Canneries continued to be segregated spaces, dispatching continued to be rife with corruption, and gangs took over the gambling rackets that the contractors had previously managed.

Young union members formed the Alaska Cannery Workers Association. In the early 1970s, the ACWA lodged grievances against Local 37 and the canned salmon industry. The organization charged that non-whites were “channeled into the lowest paying, least skilled job categories,” that there was a lower pay scale for minority employees who performed the same work as whites, and that there were very few promotional opportunities for non-whites. Additionally, the ACWA noted the segregated housing and messing facilities, company policies that prevented white and non-white employees from socializing, and “the permissive attitude of union officials in allowing the companies to abuse the rights of the workers.”

The Civil Rights movement was about to come to the salmon industry. Stay tuned for next month’s column, which details the work of young Asian-American cannery workers to desegregate Alaska’s salmon canneries.

For more information, and to find quality primary sources on Local 37, visit the Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project.