Note: This piece was originally published in the May 2015 issue of Pacific Fishing. To learn more about this early halibut prospecting trip and how the eruption at Katmai impacted Kodiak, listen to the Way Back in Kodiak episode, "Prospecting for Halibut."

"It looks like I’ll be taking the Tustumena," my friend told me over the phone this last October. She was travelling to Kodiak bearing the ashes of her longliner husband, who had died the year before. She had intended to fly to the island, but volcanic ash turned Kodiak’s unfettered atmosphere into what seemed a hazy watercolor. A fierce easterly wind whipped up century-old ash from the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes on the Alaska Peninsula, propelling it across the Shelikof Strait, circling the bays of Kodiak Island, obscuring views and halting air traffic. Ash from the 1912 eruption at Katmai, the largest eruption of the 20th century, was making life difficult on the Emerald Isle again.

I quickly noted the irony in this situation. You see, the story of Kodiak’s commercial halibut fishery had its beginning in those very ashes. And now, 102 year later, it was this same ash that hearkened back to the founding of Kodiak’s halibut industry that was preventing the scattering of this halibut fisherman’s ashes in waters that seem increasingly bereft of halibut.

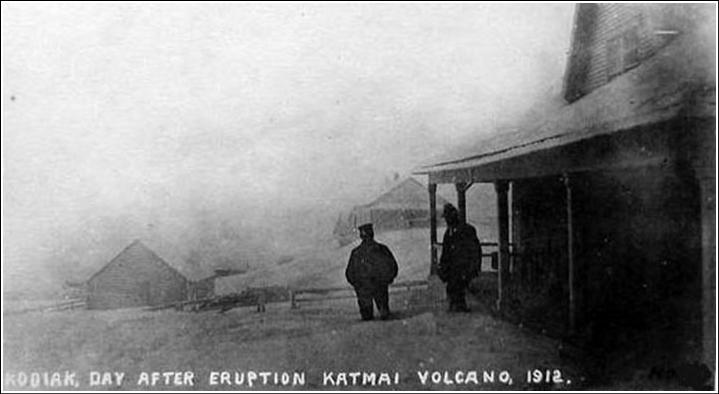

Back in 1912, ash from the Novarupta Volcano near the village of Katmai fell thick on Kodiak for three days. It was the beginning of June, a time when the sun barely sets, but no light was visible as the villagers breathed burning, sulfurous air.

This is ash, not snow. W.J. Erskine could be the man to the right, or he was the photographer. The men are standing in front of Erskine's house, which is today the Baranov Museum in Kodiak. Image courtesy USGS.

The entire village of 500 or so groped blindly through the thick fumes towards the town wharf, stumbling over the more than three feet of ash that had accumulated. The village crowded on the Revenue Service Cutter Manning which happened to be at dock. Villagers feared that another ash-induced land slide would sweep the town into the channel on which it rests. They believed that their only hope for survival was to be found at sea. Before setting out, the villagers ate boiled halibut and potatoes cooked in massive tubs. It was the first meal in days for some of them.

The boiled halibut that ravenous volcanic refugees ate a century ago had been caught during a halibut prospecting trip. Those fillets had been used to quantitatively prove that Kodiak had enough halibut to warrant a commercial halibut fishery.

The year before, in 1911, Kodiak businessman W.J. Erskine worked with the Alaska Packers Association to set up a test fishery. He enticed the Hunter and Metha Nelson, two schooners from San Francisco, to come to Kodiak to verify what the Bureau of Fisheries vessel, the Albatross, had recently uncovered: halibut fishing grounds around the archipelago. Of course this wasn’t news to Kodiak Islanders, who had been fishing and eating halibut for thousands of years, but the archipelago’s distance from any population center meant that Kodiak halibut just fed locals. Erskine wanted to demonstrate that it was possible to deliver Kodiak halibut to the San Francisco market, nearly 2000 miles away. The Metha Nelson was one of the first fishing vessels to be equipped with an on-board freezer on the Pacific Coast. Erskine was wagering that San Francisco residents would eat flash frozen halibut as an alternative to the halibut that was shipped on ice from Southeast Alaska and Puget Sound.

That 1911 season was short but decent. Erskine likely had high hopes for the 1912 prospecting trip, but it was destined to be a rough season. The engine wouldn’t run and then the engineer died. Their seine was too short to catch bait. After procuring a longer seine and bait herring, they finally started fishing. But then, just 90 miles away, a volcano blew its top.

Nonetheless, at the end of the season the Metha Nelson returned to San Francisco with 140,000 pounds of frozen halibut, which the Alaska Packers Association was able to sell. Erskine’s experiment was successful. After Katmai’s eruption, Kodiak might have been a wasteland of ash, but there seemed to be a glimmer of hope for this ravaged island. There was hope in halibut.

But that hope was not realized for decades. It was king crab, not halibut, that turned Kodiak from a summertime salmon town to a year-round fishing port, and it wasn’t until the 1960s. Kodiak also turned to shrimp in the 1970s, turning Kodiak into the "King Crab Capital of the World" and a world-class shrimp port. But then the crab disappeared, and the shrimp disappeared. Many Kodiak fishermen turned to halibut, fishermen like my friend’s husband. He and other highliners really struck gold in 1995 when halibut was rationalized and those with historically high catches were granted private stock in a public fishery resource. But, not totally unlike the boom and bust pattern evident in the crab and shrimp fisheries of the region, halibut harvests have declined over the last decade. It takes commercial halibut fishermen longer to catch their quota, sending the cost of fishing up.

But, just as the ash-ravaged landscape of Kodiak eventually was overcome again by green, biologists with the International Pacific Halibut Commission report that halibut stock is rising after a decade of decline. Perhaps, like those Kodiak villagers one hundred years ago, who, blinded by ash, sought salvation at sea, Kodiak halibut fishermen too will be in the clear.