I spent December and the beginning of January in Petersburg, relishing the tranquility of this community, partaking in the yuletide festivities (God Jul), and planning for a new book project. With humility and gratitude, I'm excited to share this project with you. Stay tuned for the coming anthology, examining Southeast Alaska canneries as sites of Alaska history, published by Shorefast Editions. Below is a taste of what is to come.

The illustrations in the book are going to be killer. Derived from the private collection of my collaborator, Karen Hofstad, there is material that will be featured that just may not exist anywhere else. Like this stamp.

In Alaska, canneries are places where fish are put into cans. But they are more than this perfunctory, mechanical description. They are places of work. They are places of leisure. They have served as prisons and relocation camps. They are where Alaskan families have been made, where technological innovations have changed the way the world eats. They are places of segregation and integration. They are the sites of “corporate mortality” and dogged persistence. They are the backdrop for the industrial revolution of the north. They are sites of racial conflict, environmental degradation and scientific hubris. Canneries are theaters of activity and places that have made, shaped, and been the setting for Alaska history.

There are a multitude of ways to consider canneries, and a multitude of historic disciplines through which they can be examined. Political, business, social, environmental, cultural, and gender history come together on the docks, on the decks, and in the mess halls. As such, this anthology will be a seafood smorgasbord, including in its interpretive stances. It will combine both micro-histories of the operations of specific canneries within Southeast Alaska with thematic, interpretive essays. It will appeal to a broad readership as a work with both historical and literary merit.

It is not the definitive history of the seafood industry in Southeast Alaska, and there is much which is not included. But it will serve as a new means of thinking and looking at the places of production, these landscapes of work, and why the places, people, and stories contained within those weather-beaten walls matter.

This book is a labor of love and truly a collaborative effort. It is written in memory of Southeast historian, Pat Roppel. For decades, Pat compiled research on the history of the seafood industry throughout Alaska, but particularly Southeast. She intended to write a book detailing cannery operations throughout the Panhandle and made it so far as to draft over 30 individual cannery histories, in addition to many short biographies of those involved in the seafood industry. But she died before her work was finished, and her papers were donated to the Alaska State Library Historical Collections.

Karen Hofstad was a close friend and collaborator of Pat’s. Over forty years ago, Karen started collecting salmon can labels, fishing industry ephemera, and other source material related to the industry in order to write a book about the history. When she met Pat, she saw that there was already a work in progress, so she shared her resources and a decades-long conversation with Pat.

After Pat’s death, Karen decided that it’s time to finish this book and invited me to take part in the project, in honor of our mutual friend. Pat wrote detailed operational histories of canneries, which are relevant to the local communities to which the canneries pertained. Karen and I decided to create something that will appeal to a broader readership. So, this anthology will incorporate edited selections of cannery histories and essays that Pat wrote with broader, interpretive essays that examine how canneries are representative of themes, events, and ideas in Alaska history.

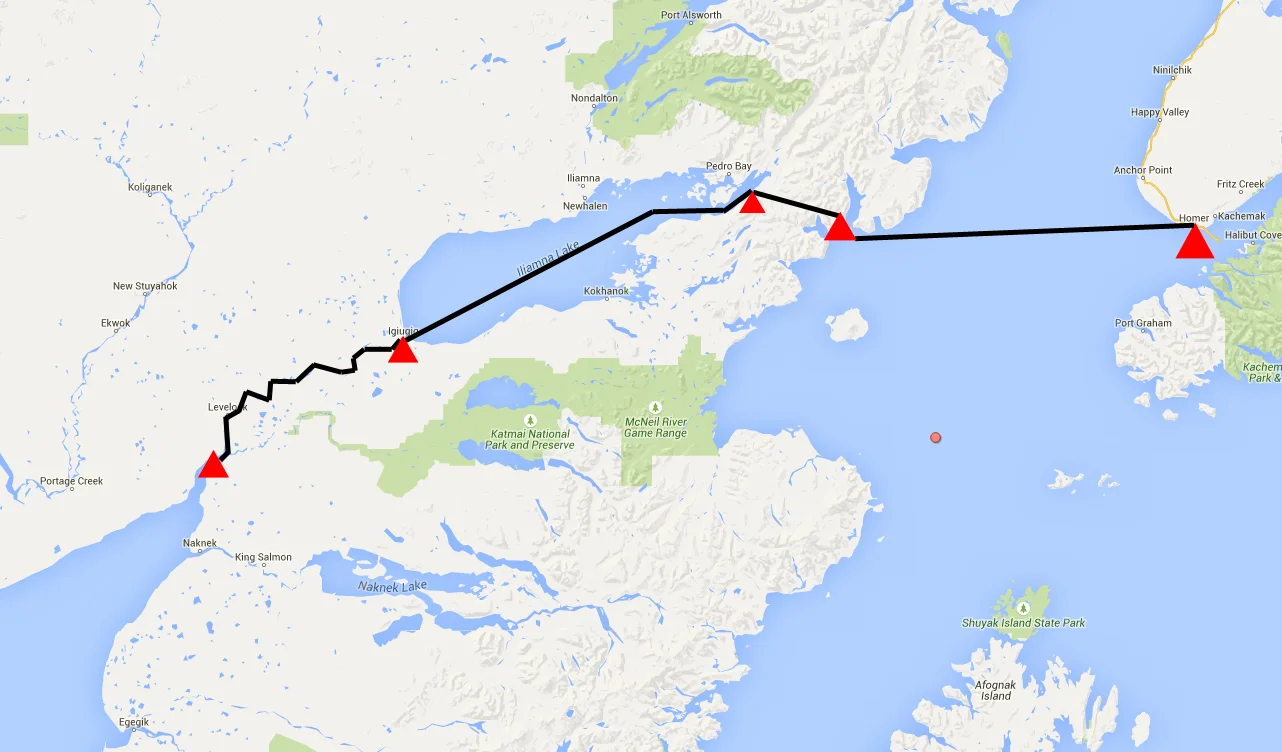

Readers will turn into time traveling cannery tourists, able to swoop from bay, to strait, to island across Southeast Alaska, touching down at different moments in time. Along the way, they will see the different ways that canneries have been utilized, and examine interactions among peoples, places, nature and technology.

Our first stops are Klawock at Prince of Wales Island and Sitka. Two canneries started in 1878 in Alaska, and they are connected through the stories of early salteries, trade, and cross-cultural relationships. These first Alaskan canneries were a harbinger for what equated the industrial revolution of Alaska. Next, we travel to southern southeast Alaska, to Metlakatla, where we will examine how two of Southeast Alaska’s major industries- timber and fish- were connected. After, we will swoop over to Loring, where we will learn about the history of the Alaska Packers Association and see how an enterprising superintendent’s invention of a floating fish trap shifted fishing methods across the Pacific Northwest .

Next, we will examine Hunter Bay, where a California company known for whaling attempted to diversify its operations into salmon. The Pacific Steam Whaling Company serves as a story of corporate mortality, as it transitioned away from one dying industry and into the palms of a capitalist dreamer whose faith in a “salmon trust” gutted Alaska’s salmon industry.

The origin of Petersburg can be directly attributed to the establishment of a cannery there, in 1898. On our stop at Petersburg, we will get a glimpse of the history of the local fishing industry through five iconic objects, with the daughter of the founder of Icicle Seafoods as our able tour guide.

Port Althrop was one of 13 canneries constructed in Southeast Alaska in one year during WWI, as the industry mobilized to feed troops and Allied nations, leading the trade journal Pacific Fisherman to claim that, “The world war has been to a great extent a war of canned foods.” In World War II, people shuffled and lives crumbled as abandoned canneries like that in Funter Bay become the frigid homes of Unangan people from the Bering Sea, forced from their homeland due to the Japanese invasion. In Wrangell, we see Japanese Alaskan cannery workers sent to relocation camps. And we see German POWs shipped to the Excursion Inlet cannery after the Aleutian Islands were retaken by the allies.

At Wards Cove, we will see how desegregation and the fight for civil rights transpired in Alaska’s canneries. Finally, we will visit Kake, which is no longer in operation but still very much loved. There we will see a community’s work to preserve its beloved cannery.

Between these destinations, we’ll pause for mug-up, an Alaska-wide cannery term that means coffee break. We will rest for poetry, we will take in recipes, we will see the first-hand accounts of those who lived in these places and in these times.

Along the way, you will find material written by me, Pat Roppel, Bob King, Katie Ringsmuth, Sue Paulson, Waynne Short, Pennelope Goforth, Jim Mackovjak, and others, handsomely illustrated with materials from Karen Hofstad’s collection.

Once published, you'll need to open a can of salmon and get your saltines. You’ll need to fortify your belly with some wild Alaskan foods before you embark on this wild Alaskan ride.

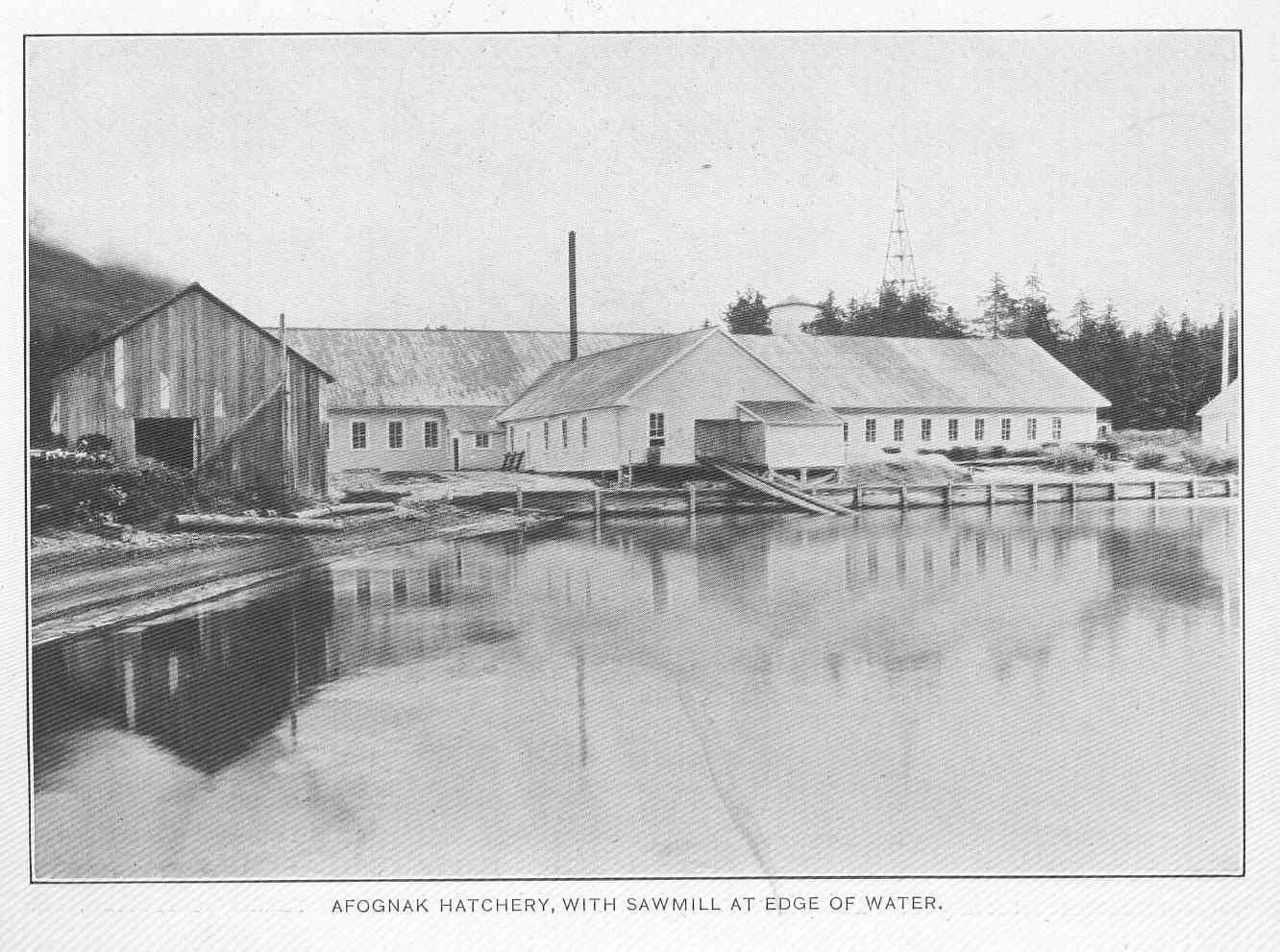

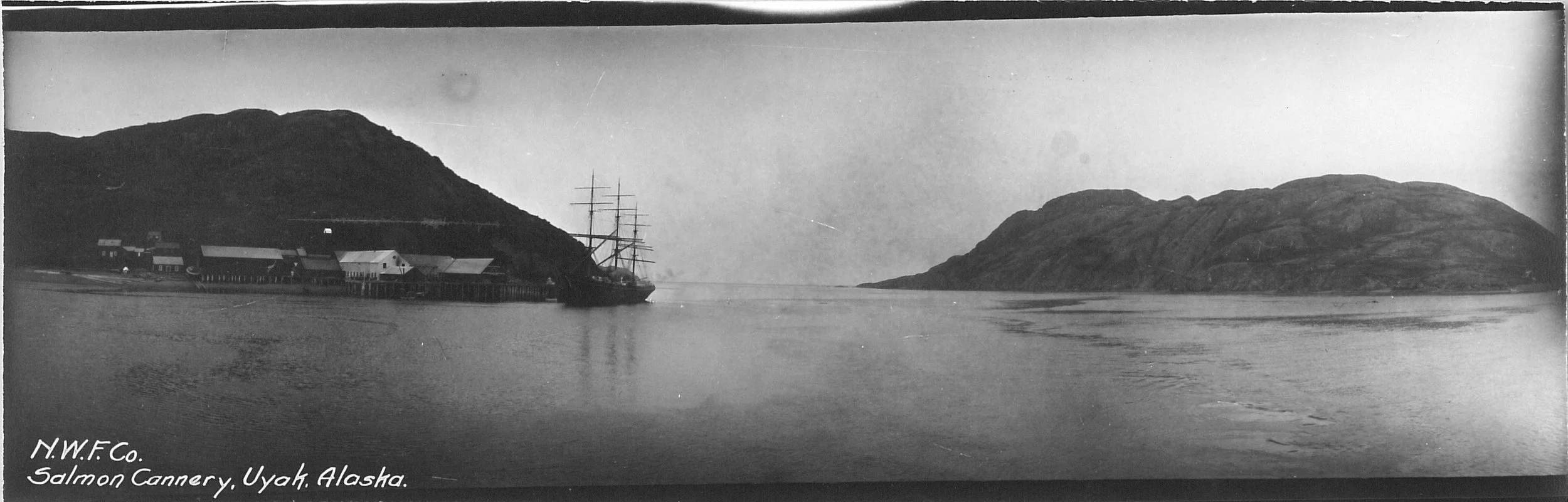

From the collection of Karen Hofstad.