Note: This essay was first published in Pacific Fishing magazine.

Last month, we learned of the connection between the Treaty of Cession in 1867 (through which the U.S. purchased Alaska from Russia) and the establishment of Alaska’s first cannery in Klawock on Prince of Wales Island in 1878. Klawock proves to be a fascinating place to examine the ways that the indigenous salmon fishery and the commercial salmon industry came together in the early days of Alaska’s seafood industry.

Early visitors to the North Pacific Trading and Packing Co. remarked on the exceptional run of salmon at Klawock. “Fish run in the vicinity of Klawock in miraculous numbers, a catch of 7,000 at a time being no unusual thing,” noted one visitor in the late 1870s. The Klawock River was so prodigious partially due to the skilled management of the salmon system by the Tlingit Gaanaxadi clan. The Gaanaxadi clan owned a resource-rich area of Prince of Wales Island around Klawock, including the Klawock estuary and the abundant herring spawning grounds nearby. Looking at historic records, it is possible to see how the Gaanaxadi clan continued to assert their rights over the fishery and persist in managing the system during the first decades of commercial exploitation of the area.

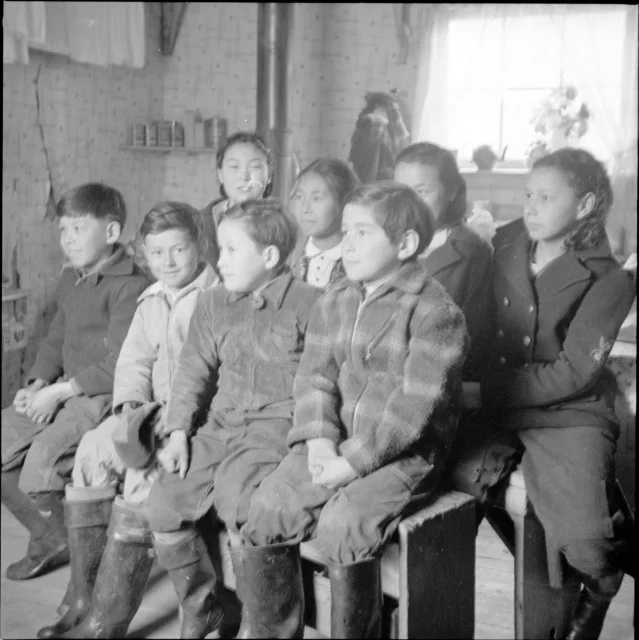

North Pacific Trading and Packing Co at Klawock in 1898, courtesy NARA.

The Tlingit had a sophisticated fisheries management structure in place in Southeast Alaska. This regime is better referred to as “engagement,” according to anthropologist Stephen Langdon, since management implies a hierarchical relationship. Tlingit fishing methods were based on a world view that perceived salmon as beings, similar to humans, who made choices, lived human-like existences at sea, and who would only return if they were treated honorably.

It was the job of the clan leaders known as héen s’aatí to determine who could fish, how the fish would be harvested, at what time, and how many. The héen s’aatí were on-the-ground fisheries managers who knew the river system and the run better than anybody else. Tlingit clans had well-developed notions of private property rights. Hunting grounds and salmon streams were viewed as clan property. The héen s’aatí determined who could access the fishing grounds.

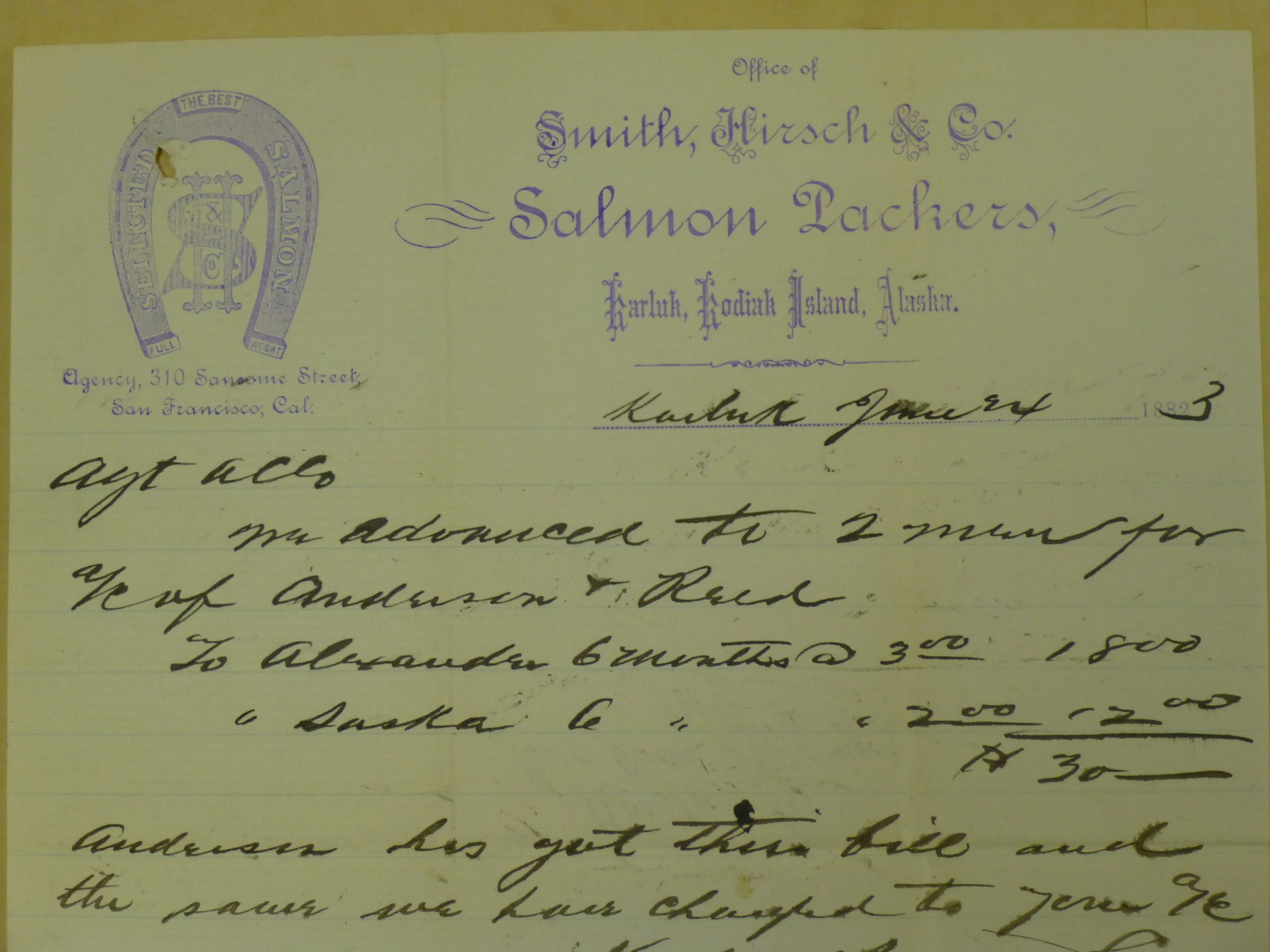

Teqahaite was the héen s’aatí in the 1880s and 1890s in Klawock, and he is reported to be the “possessor of the largest and best canoes at Klawak [sic], and claims 2 or 3 of the best fishing streams in the vicinity,” according to the 1890 census. When the North Pacific Trading and Packing Co started canning at Klawock, it seems the cannery received permission from the héen s’aatí to harvest fish and paid for the privilege, as documented in a lease agreement between the cannery and Teqahaite in the Ketchikan Recording Office. Americans relied on deeds and legal documents to ascribe title, but the Tlingit installed petroglyphs, totems, and other monuments to indicate ownership of streams. Teqahaite followed the Euro-American and Tlingit protocols, both signing the lease and installing a marble monument next to the cannery with his name on it. This monument still stands today.

There were ritual actions that ensured the salmon would return--- such as returning the bones of salmon to their home river--- but it was the work and knowledge deployed to determine fishing location, intensity, timing, and gear that ensured escapement. The héen s’aatí would oversee the preparation of the fishing gear and modify the gear based on the natural features of a fishing spot, the intensity of the run, and observed escapement. “The Klawock estuary is a highly engineered landscape,” Steve Langdon explains. “The understanding that you cannot obstruct salmon going to their homes was absolutely a critical, moral foundation for Tlingit leadership.”

The Tlingit invented trolling, but most salmon fishing occurred where the most fish conglomerate: at the intertidal zone near salmon streams and within rivers. Fishing weirs were constructed of rocks or carved wooden stakes. The walls of the weirs were constructed so that at high tide salmon could easily access their home streams. As the tide ebbed, the weirs prevented some of the salmon from surging back to sea with the tide. These fish were trapped in pools constructed behind the weirs and harvested on the beach. To create another common type of fishing weir, women wove cedar mats which were staked near streams. These systems served as removable pens for the salmon. The Tlingit converted the tidelands of Southeast Alaska into a form of fishing gear that allowed for escapement. Today, both stone and stake weir systems are evident in the tidelands throughout Southeast Alaska and near Klawock.